Common CAD Drawing Formats Explained | How To Choose The Right One?

Imagine sending a carefully crafted CAD file to your manufacturing partner only to get one word back: “Can’t open.” Frustrating, right? That scenario plays out far too often because what seems like a simple “save and send” hides a minefield of incompatible formats. Consider this: in 2024, most CAD software started supporting the DWG format, making it the most universal drawing format in use today. But universality doesn’t guarantee suitability.

In this guide, you’ll discover why some formats behave like universal languages, and why others silently erase your design’s most critical details.

We’ll walk through the most common CAD drawing formats, what each one actually stores (or discards), and most importantly, how to pick the right one so you avoid hidden pitfalls. Buckle up: this isn’t just theory. It’s your CAD-file handshake with the real world.

What is a CAD file format?

- A CAD file format is the container that holds the entire “mind” of your design. Open one up (figuratively), and you’ll find far more than just lines and shapes. It stores geometry with every edge, curve, and surface that gives the object its form. It keeps metadata, too: units, materials, part names, even the designer’s notes. Many formats also hold layers for organizing drawings, PMI (Product Manufacturing Information) like tolerances or weld symbols, and full assemblies that define how multiple parts fit and move together. In other words, a CAD file isn’t just a picture; it’s a blueprint with memory.

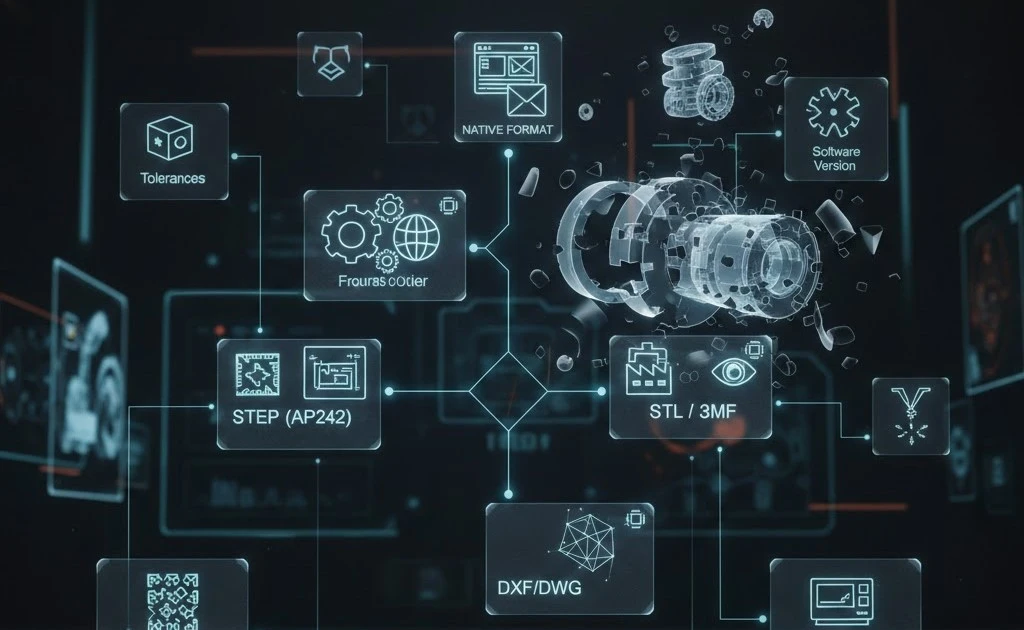

- So why do formats differ so much? Because each one is built with a different purpose in mind. Native formats prioritize software-specific features and parametric history. They’re powerful, but often locked inside a particular ecosystem. Exchange formats focus on portability. This translates to trading off some details to travel safely between different CAD platforms. And mesh formats take a completely different route, breaking geometry into tiny triangles to maximize visual or 3D-printing fidelity.

- That’s why choosing the right CAD files format matters. Not all containers carry the same cargo, and what they leave behind can change everything.

The Three Practical Format Categories

Before you explore CAD extensions, it is necessary to see the big picture. Nearly every CAD file you’ll ever handle falls into three categories. Each comes with its own logic, strengths, and limitations. Think of them as three different languages spoken across the design world.

Native / Authoring Formats

DWG, SLDPRT, IPT, and CATPART are the first ones. These are the “home languages” of major CAD systems. When you work inside AutoCAD, SolidWorks, Inventor, or CATIA, this is the format where your design is born and where it’s happiest. Native files preserve everything: parametric history, constraints, feature trees, sketches, mates, custom properties…the works. The drawback? They tend to be loyal only to the software that created them. Open them elsewhere and you may lose intelligence, structure, or the ability to edit deeply. Full fidelity, yes. True portability, not so much.

Neutral / Exchange Formats

STEP (.stp/.step), IGES (.igs/.iges), Parasolid (.x_t), ACIS (.sat). These formats exist for one mission: communication between different CAD ecosystems. They strip away software-specific tricks and translate your model into geometry most platforms can read. Assemblies can survive the trip, and the core shape usually comes through intact. But translation isn’t magic; sometimes tiny gaps appear, surfaces misbehave, or metadata gets left behind. It’s the price of diplomacy.

Tessellated / Mesh Formats

STL, OBJ, 3MF are all about the world of triangles, color maps, and lightweight geometry. Instead of analytic surfaces and edges, these formats convert your model into a mesh. Perfect for 3D printing, rendering, or quick visual checks. But they forget the deep intelligence behind your part. No parametrics. No history. No assemblies with mates or motion. Just the shell. If you need to manufacture or modify the design later, these formats won’t tell the whole story.

Quick Reference Table

Below is a clean breakdown of what the most common extensions actually represent, what they’re best used for, and whether they keep the all-important parametric intelligence that many workflows depend on.

| Extension | Category | Primary Use Case | Keeps Parametrics? | Common Software Support |

| DWG | Native/Authoring | 2D/3D drafting, architectural drawings, engineering layouts | Yes (in native environment) | AutoCAD, BricsCAD, DraftSight |

| DXF | Native/Exchange | CNC, laser cutting, simple 2D/3D exchange | Partially (limited) | AutoCAD, Fusion 360, SolidWorks, CNC software |

| STEP (.stp/.step) | Neutral/Exchange | Manufacturing, cross-platform sharing, assemblies | No (but geometry preserved) | SolidWorks, Inventor, CATIA, Siemens NX, Fusion 360 |

| IGES | Neutral/Exchange | Legacy surfaces, wireframes, older workflows | No | Many major CAD programs (mixed reliability) |

| Parasolid (.x_t) | Neutral/Kernel | Precise solid geometry exchange | No (but excellent geometry fidelity) | SolidWorks, Solid Edge, NX |

| ACIS (.sat) | Neutral/Kernel | Solid modeling exchange | No | AutoCAD, BricsCAD, others using ACIS kernel |

| STL | Mesh/Tessellated | 3D printing, slicing, quick visualization | Not at all | All major 3D printing tools & viewers |

| OBJ | Mesh/Tessellated | Rendering, 3D scanning, color texture models | No | Blender, Maya, 3ds Max, printing tools |

| 3MF | Mesh/Tessellated | Advanced 3D printing with colors, units, metadata | No | Windows 3D Builder, PrusaSlicer, Cura, others |

Deep-Dive Into The Formats You’ll Actually Encounter

Once you move past the theory, you start to see the real landscape engineers stumble through every day. Some formats behave beautifully, others act like cranky old machines, and a few only make sense once you’ve ruined a weekend trying to fix a corrupted export. This section unpacks each major format group the way designers actually experience them—warts, wonders, workarounds, all of it.

DWG & DXF

DWG: The Native Heavyweight

DWG is AutoCAD’s native heartbeat. Fast, compact, unapologetically tied to the Autodesk universe. It stores 2D and 3D vectors, layers, annotations, blocks, layouts, and all the behind-the-scenes logic that makes a drafting file editable and “alive.”

Use DWG when you’re operating inside an Autodesk environment or passing files to someone who definitely uses software that understands DWG with no translation gymnastics. It’s the closest thing to handing over the original blueprint of your project without losing any detail.

Pros:

- Compact binary format with small file sizes, fast loading

- Keeps layer structures, references, annotation intelligence

- Perfect for ongoing collaboration in AutoCAD/BricsCAD

Cons:

- Proprietary ecosystem; not every tool handles DWG the same

- It can become glitchy when translated into non-Autodesk tools

- Complex drawings sometimes lose intelligence when exported elsewhere

Practical tip: If you want zero surprises, stay in DWG or confirm the recipient’s software and version. Yes, version sometimes matters more than the file itself.

DXF: The “Universal-ish” Exchange Cousin

DXF was Autodesk’s attempt to build a more open language which is something readable by almost anything. These are ideal for mobile CAD And it largely succeeded in universal compatibility. DXF comes in ASCII or binary, can be opened by an enormous range of programs, and is a staple for CNC, laser cutting, plasma machines, and even GIS workflows.

But being universal comes at a cost. DXF can explode into huge file sizes. Some CAD features don’t translate cleanly. Blocks can unravel. Hatch patterns may misbehave. And 3D DXFs? They work, but not gracefully.

Pros:

- Excellent for manufacturing workflows that need pure geometry

- Supported by nearly every CAD, CAM, and CNC tool

- Easy to inspect, easy to salvage

Cons:

- Can balloon into massive ASCII files

- Feature data often gets flattened or lost

- 3D support is inconsistent

Practical tip: Export as DXF R2013 (or a version specifically requested). It’s the sweet spot between compatibility and geometric reliability.

Call Us And Get A Quote For The Perfect CAD Draft

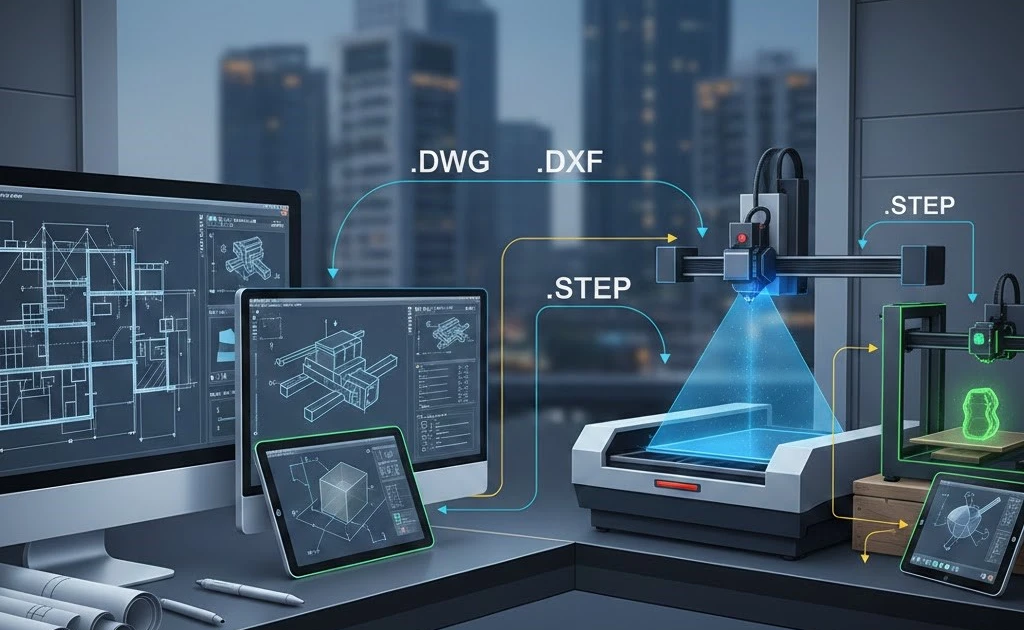

STEP (.step / .stp): The “Go-To” Exchange Format

STEP is the international diplomat of CAD formats. Neutral, widely supported, surprisingly robust, and the closest thing the CAD world has to a “safe default.” A good STEP file carries solids, surfaces, assemblies, and even PMI—depending on the AP version used.

AP203, AP214, AP242; no, these aren’t robot model numbers. They’re STEP “Application Protocols,” and they matter.

- AP203: geometry + basic structure

- AP214: automotive workflows, colors, layers

- AP242: geometry + rich PMI + better assembly handling

For most modern engineering needs, AP242 is the one that keeps your tolerances, callouts, and manufacturing logic safest.

Why STEP dominates:

- Vendor-neutral

- Reliable geometry transfer

- Great for CNC machining, fabrication, and supplier hand-offs

- Handles multi-part assemblies without throwing a tantrum

Downsides?

- No parametric history

- Occasional tiny gaps or surface anomalies after import

- File structure isn’t as compact as native kernel formats

Practical tip: If a supplier doesn’t specify a format, send STEP. If precision tolerances matter, ask for or export using STEP AP242.

IGES (.igs / .iges)

IGES is the grandparent of neutral CAD formats, still wandering around the industry, still used, still occasionally surprising. It’s great with surfaces and curves, and some old workflows depend on it. But IGES doesn’t understand the modern need for PMI, assembly structure, or rich metadata.

So why is it still around? Because some sectors, especially legacy aerospace and automotive environments, never fully abandoned it.

Strengths:

- Fantastic for complex surface models from older systems

- Produces relatively small files

- Supported by almost every CAD tool

Weak spots:

- Does not carry parametric or PMI data

- Assemblies often flatten or break

- More prone to translation inconsistencies than STEP

Use IGES when you’re dealing with old systems, unusual surface models, or a partner who specifically requests it. Otherwise, STEP is almost always the smarter move.

Parasolid (.x_t / .x_b) & ACIS (.sat)

These formats don’t represent software platforms; they represent modeling kernels, the engines inside many CAD systems. Parasolid powers SolidWorks, Solid Edge, and Siemens NX. ACIS shows up in AutoCAD, BricsCAD, and others.

When you export in .x_t, .x_b, or .sat, you’re talking directly to the kernel. You’re giving the receiving software highly precise B-rep geometry, the clean mathematical surfaces used for manufacturing-grade modeling.

Parasolid strengths:

- Excellent precision

- Strong interoperability between Parasolid-based systems

- Compact, stable, predictable

ACIS strengths:

- Clean solid modeling fidelity

- Great for DWG-based environments

Limitations for both:

- Still no parametric history

- Not ideal for exchanging PMI-rich or assembly-intelligent files

- Only truly shines when both sender and receiver use the same kernel family

Practical tip: Use a kernel format when two collaborating teams rely on software built on the same modeling engine. It’s like speaking directly in their native dialect.

STL, OBJ, 3MF: 3D Printing & Visualization Formats

STL

STL is simple: it converts your perfectly smooth CAD model into a cloud of microscopic triangles. No curves, no features, and no tolerance, just facets. This is ideal for 3D printing because slicers adore meshes, but it also means you’re throwing away nearly all engineering intelligence.

Pros:

- Universally accepted in the 3D printing world

- Fast, lightweight, easy to process

- Great for prototypes and visuals

Cons:

- No units

- No PMI, no materials, no assembly structure

- Thin features can distort or disappear

Tip: Always confirm units with the recipient. An inch interpreted as a millimeter is a nightmare you won’t forget.

OBJ & 3MF: The More Modern Mesh Options

OBJ brings color, textures, and UV maps to the party, making it a favorite in 3D scanning, AR/VR, and visualization. But it still doesn’t store manufacturing intelligence.

3MF, on the other hand, is the mesh world’s rising star. It stores:

- Units

- Colors

- Materials

- Print settings

- Multiple bodies or components

It’s dramatically more capable than STL, and many modern printers prefer it.

When to use:

- Use STL for simple prototypes and basic prints

- Use OBJ for full-color or texture-heavy models

- Use 3MF when you want metadata, accuracy, and a cleaner workflow

Practical tip: When sending mesh formats for printing, include the intended resolution and minimum feature size. Not all printers can read between the triangles.

How to Choose the Right Format: A Decision Flow

Choosing a CAD format doesn’t have to feel like decoding an ancient manuscript, although it often does. The trick is to think in terms of intent. What are you trying to communicate; intelligence, geometry, surfaces, or just triangles? Once you identify that, the right format usually emerges on its own. Here’s a compact decision flow that behaves more like a practical compass than a formal flowchart.

Quick Decision Flow

● Staying inside the same CAD system? Use the native format!

Keep everything intact including history, constraints, features, sketches, behaviors. This is your safest, smartest move.

Tip: If you hand off a parametric model, mention which add-ins or templates you used; it prevents version shock on the other end.

● Cross-CAD engineering or manufacturing exchange? Choose STEP (preferably AP242)!

It moves solids and assemblies reliably and gives suppliers fewer reasons to call you at 2 a.m.

Tip: Always include tolerances, datums, and GD&T as separate PDFs or PMI if the receiving system supports it. STEP carries a lot, but people like clarity.

● Sending to a 3D printer or visualization pipeline? STL (or 3MF if metadata matters)!

Meshes travel fast, but they forget everything about how your model works. That’s fine for printing or rendering.

Tip: For STL, specify units in your message and include the desired mesh resolution; coarse meshes can destroy fillets or thin ribs. 3MF avoids unit ambiguity, so use it whenever your printer or service accepts it.

● CNC routing, laser cutting, plasma, waterjet, or clean 2D plans? DXF/DWG (confirm version)!

These formats feed manufacturing machines geometry they understand without translation drama.

Tip: Send flattened sheet-metal patterns as separate files. Many shops prefer DXF R12/R2013. Remove construction lines unless the machinist specifically wants them.

Common Pitfalls & How to Avoid Them

Most of the common CAD drafting mistakes come from predictable traps, and once you see them a few times, you start to anticipate them like weather patterns.

Unit Mismatches: mm vs. inches

This is the classic blunder. A model meant to be the size of a coffee mug suddenly imports at the size of a grain of rice, or a refrigerator. Units don’t always travel with the file, especially in STL or older DXF exports.

Solution: Always declare units explicitly in your communication or even the filename. Something like Bracket_A_v4_25mm.STEP or Housing_inch.STL saves everyone from scaling nightmares.

Missing PMI or Tolerances

You expected full GD&T, datums, and callouts—and the recipient sees a naked solid with zero context. That’s usually because the wrong export flavor was used.

Fix: Ask for STEP AP242 if PMI matters, or request the native CAD file plus a separate PDF for dimensions. Redundancy protects you when the translation pipeline decides to drop something important.

Bloated DXF Files

DXFs written in ASCII can balloon to absurd sizes. A simple sheet-metal pattern becomes a monster that takes minutes just to open.

Workaround: Switch to DWG for transmission or export a binary DXF if the workflow insists on DXF. Compression helps, but using a smarter format helps even more.

Assemblies Flattening into a Single Part

You send a lovely multi-body assembly, complete with proper relationships, and the receiver gets a monolithic blob. This usually happens when exporting to formats that don’t carry assembly logic, or when someone accidentally exports the top-level body instead of the structure.

Avoidance:

- Export assemblies as STEP with assembly mode enabled.

- Provide a simple exploded view PDF so the receiver knows what goes where.

- If manufacturing is involved, send each part as an individual file plus one assembly file for reference.

What You Should Clarify With Any Supplier (In Prose, Not a Checklist)

Before sending anything out, have a short, direct conversation with your supplier. Ask them which exact formats their equipment prefers, which versions they can reliably import, whether they need PMI embedded or provided separately, and if their workflow interprets units automatically or requires manual confirmation. It’s worth asking how they handle assemblies. Some shops want one file, others insist on separate solids. And always confirm the minimum feature size their tools can handle; there’s no point sending beautifully modeled micro-details that their machine simply cannot produce.

Conversion Best Practices & Tools

Converting CAD files is a bit like moving houses. A deliberate workflow saves massive headaches. Especially when you’re juggling multiple formats or collaborating across different software ecosystems. The goal isn’t just “get the file to open”; it’s “get the file to open correctly.”

Smart Tools & a Safer Workflow

Whenever possible, let the native CAD system generate the export. That’s where the model knows who it really is. These are usually ideal for as-built drawings. That’s where the system includes features, tolerances, references, and all the subtle geometry that translators sometimes squash. If you’re jumping between platforms, open the exported file in the target software immediately. Don’t assume it will interpret curves, trimmed surfaces, or complex assemblies the way your original did.

For large or delicate assemblies, consider using dedicated translators or built-in conversion kernels instead of the quick-export button. They tend to handle joints, mates, and multi-body structures with fewer surprises. Even a simple neutral viewer (the kind that only cares about geometry) helps you verify what survived the trip. Think of it as checking your luggage before leaving the airport.

Quick Sanity Checks After Every Conversion

A fast inspection routine will save you from embarrassing calls from machinists or suppliers who found something weird at the worst possible moment. After you convert, run through these essentials:

- Open the file fully in the receiving software. Watch for missing references or suppressed features.

- Check critical dimensions. Even a 0.2 mm deviation can ruin a precision part.

- Inspect holes, threads, and fillets. These areas like to deform or lose definition during poor translations.

- Verify assembly structure. Are components in the right position? Did mates survive? Did anything explode into space?

- Confirm PMI, GD&T, and BOM data. Some formats drop annotation intelligence silently.

- Look for gaps, seams, or surface tears. Kernel mismatches tend to show up here.

FAQ

What format should I send to a manufacturer?

Usually STEP (AP242), unless they specifically ask for the native file their machines already speak fluently.

Does STL keep tolerances or GD&T?

Not at all. STL is a triangle soup. For tolerances, stick with STEP or a native CAD format.

Can I convert DWG to STEP?

Yes, you can export or convert through most CAD systems. But always open the resulting STEP to make sure nothing warped.

Is DXF still good for laser or CNC cutting?

Absolutely. DXF remains a shop-floor classic. Just confirm the version they prefer before sending it.

Why did my assembly import as a single lump?

The export likely flattened it. Re-export using assembly mode in STEP, or share each part separately.

Which format should I use for 3D printing?

STL for quick prints, 3MF when you need colors, units, or print metadata.

Can IGES still be useful today?

Yes, especially for older systems or surface-heavy workflows. But STEP is more reliable for modern engineering.

Why do my file sizes explode when exporting DXF?

ASCII DXFs can get huge. Switch to binary DXF or use DWG to shrink the payload.

Do mesh formats keep parametric history?

No. STL, OBJ, and 3MF forget everything behind the shape. They’re geometry-only travelers.

The Bottom Line

Choosing the right CAD format isn’t magic. On the contrary, it’s matching the file to the job. Native files keep your parametrics alive inside your own team. STEP holds up beautifully when you cross software boundaries or hand work to a manufacturer. Mesh formats like STL or 3MF strip the model down for printing, visualization, and anything that doesn’t need history or intelligence. No matter what you send, make life easier for everyone by stating your units, noting any critical tolerances, and mentioning the software version you used. It’s incredible how much friction disappears when you share those three details.

One-liner rule: Keep native internally, use STEP for manufacturing and collaboration, and choose STL/3MF when you just need a clean mesh for printing or visuals.